The project team included (pictured left to right) Juliana Landis, Environmental Sciences and Economics from the University of Vermont; Julia Tricca, Art and Environmental Studies from Clark University; Dana Barnes, Psychology and Architecture from the University of Hartford; Kelly Li, Architecture at Carnegie Mellon University

by Kelly Li

In early April, I traveled to Princeton University to participate in their Environmental Institute’s second annual Environmental Ideathon, a 36-hour workshop to brainstorm environmental strategies for cities around the world. The event took place April 5-7, 2019 under the theme Green Metropolis. I enrolled in the competition with a group of three other students I befriended while abroad in Berlin: Juliana Landis, Environmental Sciences and Economics from the University of Vermont; Julia Tricca, Art and Environmental Studies from Clark University; and Dana Barnes, Psychology and Architecture from the University of Hartford.

The conversations around “environmental” or “sustainable” strategies are broad and widely discussed — as I think they should be — but also difficult to maneuver, with differing opinions over culprits, values, and solutions (if you think solutions exist at all). My expectation of this event was immediately questioned when brought up with a mixture of people from various disciplines and ideologies, which ultimately highlighted to me how murky and contentious the ideas surrounding the environment are.

The weekend consisted of an evening of introductory lectures alongside an initial problem statement, followed by a full day of workshops and proposal developments to be presented on April 7. Talks included those by Dickson Despommier, Emeritus Professor at Columbia University, dubbed the “Father of Vertical Farming”, and Mahadev Raman, a Director at Arup Group. The workshops ranged from product lifecycle analysis to motivational behavioral theories, often emphasizing the underlying goal of triple bottom line: environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Each student team was assigned a different city and encouraged to focus on either waste, water, food, energy, or transportation. Our team — nicknamed GAÏA for the ecological principle proposed by James Lovelock — was tasked with brainstorming environmental strategies for the city of Lagos, Nigeria. At the end of the weekend, we proposed our idea of a “Raft City.”

The team proposed the project “Raft City” as an environmental strategy for the city of Lagos, Nigeria. The project was the team’s attempt at a holistic, contextualized, and feasible strategy for social, economic, and infrastructural development.

For context — Lagos is one of the fastest-growing cities in the world with a population of 21 million, which is expected to double by 2050. Lagos is also a city characterized by its relationship with water (“lagos” means lake), with the Gulf of Guinea to the south and the Lagos Lagoon to the east. The city gets over 60 inches of rainfall a year, the bulk of which occurs during the rainy season and causes substantial damage to the informal housing that much of the city consists of. Lagos is trying to cope with expanding land use, lack of water infrastructure, lack of transportation, and income inequality, but urban growth is so rapid that strategies from authorities and city planners often become obsolete before implementation.

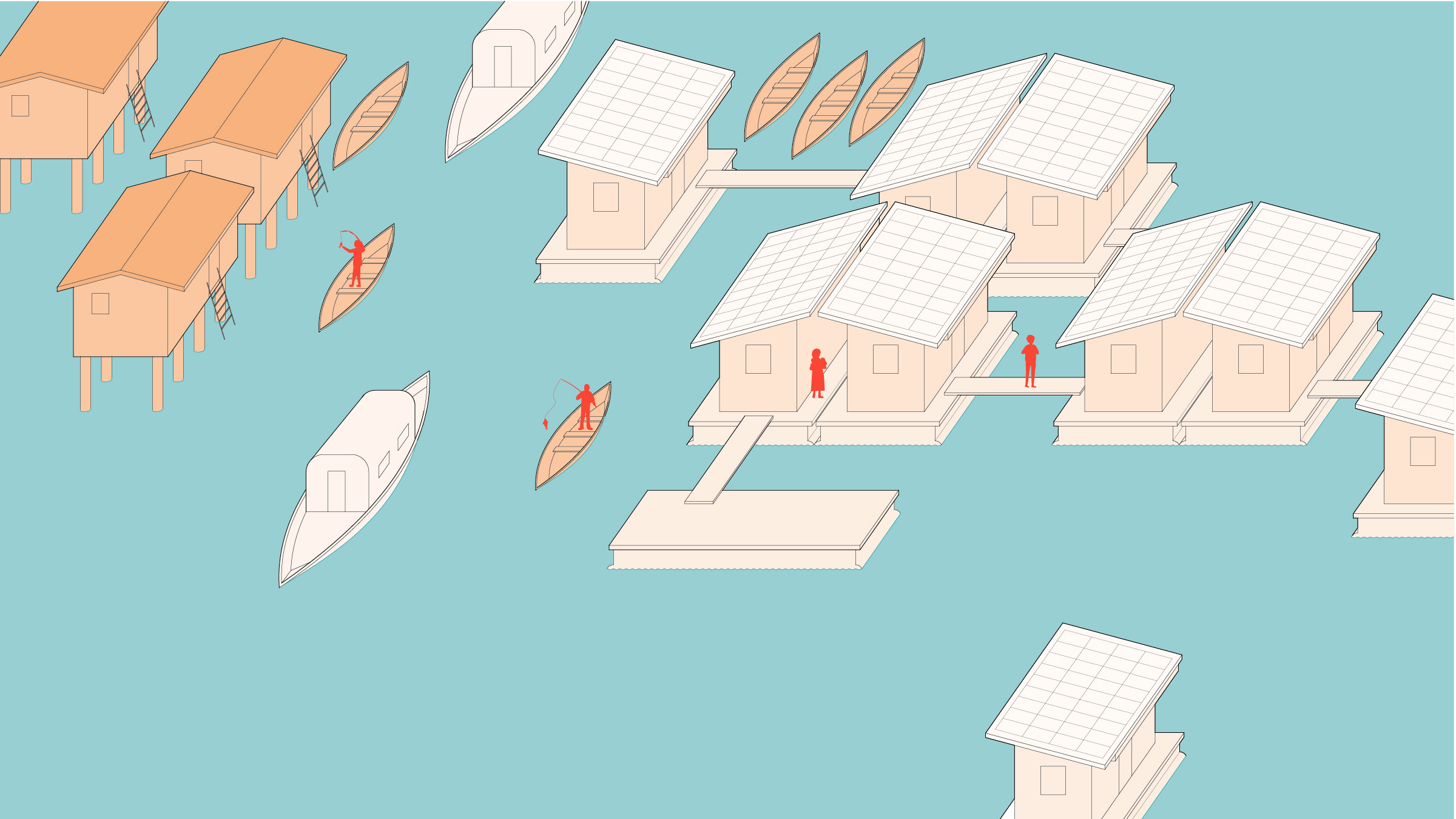

Makoko is one of the poorest, largest, and densest neighborhoods of Lagos. Makoko has a long history on the water as a fishing community, with most residents living on stilted structures above the water accessible only by boat. However, recent population growth has turned Makoko into a polluted urban slum sitting on top of contaminated water. With these considerations in mind, our group proposed a government program that could address the basic needs of Lagosians in-flux (whether due to economic, housing, or immigration status) until they were able to transition to more permanent settlements. This program would be an exchange between micro-communities and the city in the form of housing and self-sustaining infrastructures in exchange for recipients providing their manual or intellectual labor back to develop mainland infrastructure for the city of Lagos.

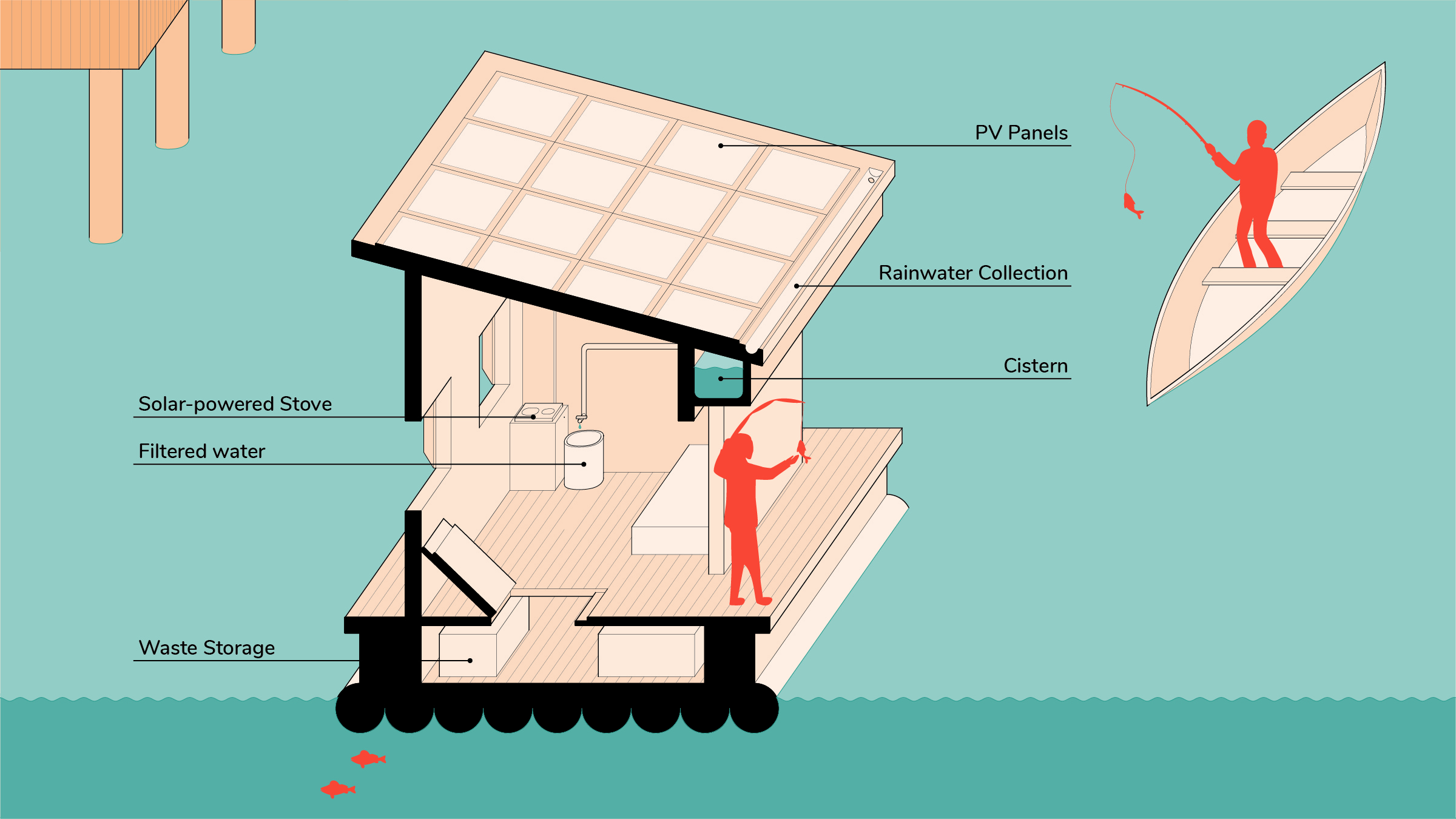

One half of this program would give self-sustaining modular infrastructures to micro-communities. Groups of Lagosians who apply could receive a series of floating structures that work together as a kit of parts to provide shelter, water-harvesting, food, energy-generation, and community spaces. These structures could combine to form larger spaces, move to adapt to changing needs, survive the flooding season, and detach to provide emergency services for other parts of the city. Through their aggregation, these rafts would be a type of mini “raft city.” The other half of this program would require recipients to develop a skill set to give back to the community through their manual and intellectual labor, a type of educational incubator which could rely on local professionals from Nigeria coordinating with Lagosians to develop skills. This has the potential to create the necessary labor force for building this modular housing or expediting mainland longer-term infrastructure projects, decreasing pressure on Lagos’ systems as a whole, and providing opportunities for newcomers to have short-term solutions on the water before moving into permanent settlements on land.

Lagos has had past initiatives to develop community spaces on the water, like their Floating School, along with an existing and robust saw mill industry in Makoko. Our team’s approach tried to tap into the existing sociocultural context while providing much-needed temporary housing and self-sufficient decentralized infrastructures aiding with water, food, and energy. These water communities would develop concurrently within a network of improvements to the city’s urban development. “Raft City” was our attempt at a holistic, contextualized, and feasible strategy for social, economic, and infrastructural development.

At the end of the weekend, our group did not end up placing in the event. The winning team proposed a detailed model outlining the specific impacts of eliminating single-use food containers in Beijing. While I was initially disappointed that the judging criteria focused on metrics over the creativity of the proposed idea, I also realized that the judging decisions by a group of professional men (there wasn’t a single woman on a judging panel of eight or so people) didn’t undermine the goals our team, alongside many of the other groups, were striving for.

I was grateful for the opportunity to work alongside motivated students from completely different backgrounds, all similarly concerned about the need for changing the trajectory of rapid climate change. This Environmental Ideathon is rooted in the belief that collaboration across fields is necessary for the larger global imperative for strategies dealing with the immense effects of the Anthropocene. At the same time, it also highlighted to me how much still needs to be done. Even at one of the most prestigious universities in the world, I was struck by how tame the suggestions were (removing plastic and promoting vertical farming are great steps, but they won’t fix all of our problems). As populations, economies, and unsustainable practices all continue to grow exponentially, the pressure on finite resources and the urgency to address these impacts will also increase exponentially.

There will always be so much progress to be made, and I’m glad to have learned from this experience. Ultimately, I left with the takeaway that we need to learn how to work together — I mean really, actually work together. While this weekend was just one micro-snapshot, it still became clear to me how much fragmentation there is. Despite a proliferation of diverse, concurrent initiatives, many are completely unaware of one another. Architecture school prides itself on teaching holistic thinking and bringing disciplines together, and I hope that moving forward, we can really learn how to grow alongside others rather than simply gleaning inspiration from them. Environmental issues are already global and already crucial, and we need to learn how to talk to one another to debate ideas, implement collective change, and propose systemic alterations to the status quo.

Kelly Li graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture and B.A. in Social & Political History from Carnegie Mellon University in 2019.